Quaternaglia (Remaster 2019)

HEITOR VILLA-LOBOS (1887-1959)

BACHIANAS BRASLEIRAS Nº1 (1930)

(arrangement: Sérgio Abreu)

- Embolada (Introdução) | 6:43

- Modinha (Prelúdio) | 6:39

- Conversa (Fuga) | 4:17

- A LENDA DO CABOCLO (1920) | 3:28

(arrangement: Eduardo Fleury)

LEO BROUWER (1939)

- PAISAJE CUBANO COM RUMBA (1985) | 7:33

- TOCCATA (ed. 1988) | 2:13

IGOR STRAVINSKY (1882-1971)

8 PEÇAS (1915-1917)

(transcrição: Paulo Porto Alegre)

- March | 1:09

- Waltz | 1:35

- Polka | 0:52

- Andante | 1:21

- Espanõla | 0:59

- Balalaika | 0:44

- Napolitana | 1:14

- Galop | 2:04

ESTÉRCIO MARQUEZ CUNHA (1941)

- SUITERNAGLIA (1993) | 6:01

(first recording)

LEO BROUWER (1939)

- PAISAJE CUBANO COM LLUVIA (1984) | 7:42

total: 55:10

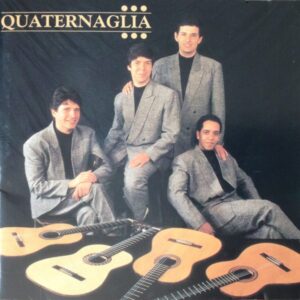

Quaternaglia Guitar Quartet

Breno Chaves / Eduardo Fleury / Fabio Ramazzina / Sidney Molina – guitars

Audio Engineer: José Luiz Costa (Gatto)

Musical Producer: Edelton Gloeden

Recorded at: Igreja Escandinava de São Paulo (Feb. 10-16, 1995)

Assistent: Nelson Pereira dos Santos

Guitars by: Sérgio Abreu (Chaves, 1989; Fleury, 1988; Ramazzina, 1991; Molina, 1992)

Cover Photo: Gal Oppido

Texts by Sidney Molina / Sérgio Abreu / Gilberto Mendes

Leo Brouwer’s works have largely contributed to spread and stabilize the formation of guitar quartets as an interesting chamber proposal which is more and more present in the international musical scene. The three pieces correspond to the author’s present esthetical concerns – the oldest one was created over 10 years ago – but they preserve important influences from previous phases of his composing path, that is that of a late romanticism with national Latin American qualities (the fifties-sixties) and that of radical vanguard experiences (the sixties-seventies).

Minimalism and the use of exotic scales must be emphasized as some of the main influences present in his work for quartet.

Paisaje Cubano con Rumba was written at first for Franz Brügen’s flute quintet and later it was adapted by the author for guitar quartet as well as for guitar solo and magnetic tape. Together with Paisaje Cubano con Lluvia and with Paisaje Cubano con Campanas (1986) for guitar solo we have the series of “Paisajes”. Brouwer offers the possibility of having more than four instrumentalists performing these pieces.

Estércio Marquez Cunha, a Brazilian composer, is a Doctor of Arts by the University of Okhahoma (USA) and a teacher at Universidade Federal de Goiás. Besides Suiternaglia, his repertoire for guitar includes two pieces for guitar solo, music for guitar and violin, three pieces for soprano, flute and guitar, and music for two guitars.

On Suiternaglia the author says: “Suiternaglia was written for four guitars (especially for Quaternaglia) in three continuous and inseparable movements. Basically moulded on the same elements, each movement preserves its own emphasis: the first one is melodious, the second one is full of timbre and the third one is rhythmical”.

Lenda do Caboclo was written by Heitor Villa-Lobos for piano solo in 1920. Choros nº1 for guitar solo was written in the same year and as far as the piano work is concerned we can find Lenda do Caboclo between Prole do Bebê nº1 (1918) and nº2 (1921), a period before Villa-Lobos’ participation in Semana de Arte Moderna de 1922 in São Paulo and his first trip to Paris (1923). Eduardo Fleury did the transcription for guitar quartet.

The series of 9 Bachianas Brasileiras (1930-45) was conceived by Villa-Lobos as a dialogue between the universality of J.S. Bach’s work (1685-1750) and the Brazilian popular music of the first half of the century. Bachianas Brasileiras nº1 shows this intention in the double titles of the movements: “Introdução” connected with the rhythm of “emboladas”, “Prelúdio” with the melodism of “modinhas” and “Fuga” with a “talk” between four “Chorões” from the city of Rio de Janeiro of the beginning of the century. Dedicated to Pablo Casals it was originally composed for 8 cellos and it was performed for the first time in Rio de Janeiro and directed by Walter Burle Max. On this recording, Quaternaglia performs Sergio Abreu’s transcription, a Brazilian guitarist and luthier.

Igor Stravinsky wrote Three Pieces for Piano at Four Hands in 1915(March dedicated to Alfred Casella, Waltz to Eric Satie, and Polka to Serge Diaghilev) and 5 Pieces for Piano at Four Hands in 1917(Andante, Española, Balalaika, Napolitana and Galop), in a piano hiatus between the 4 Studies op7 (1908) and Piano Rag-Music (1919). Almost simultaneously he did the orchestration of these 8 pieces now divided into two suites: nº 2 (1921) containing March, Waltz, Polka and Galop and nº 1 (1925) with Andante, Napolitana, Española and Balalaika.

These 8 Pieces were successfully performed by the famous Aguillar Lute Quartet during tours all over Europe and in North and South America in the twenties and thirties. These Spanish musicians were praised by the famous Brazilian writer Mario de Andrade when they presented their concerts in São Paulo in 1933. The first recording for guitar quartet dates from 1976 and was performed by the Argentinian quartet Martinez-Zárate. This present version was conceived from the original for piano at four hands by the Brazilian guitarist Paulo Porto Alegre who also did the transcription and the recording of some of these pieces for guitar trio (Trio Opus 12, 1982).

Sidney Molina

_____________________________________________________________________

I had already heard Quaternaglia playing in Santos, at Teatro Municipal, and the concert really interested me with Stravinsky’s, Villa-Lobos’ and Brouwer’s pieces. A live interpretation full of youth. Now we have this CD that shows this group’s talent and serious work. It is a group that knows how to choose its repertoire and perform it perfectly both technically and intellectually. I think the best we can do is to sit and hear so as to enjoy this good music.

Gilberto Mendes

_____________________________________________________________________

The origins of putting together the most different musical instruments with the aim of exploring possibilities of sound combinations date from the birth of music itself, even with its most primitive forms. Therefore, it’s not surprising at all the fact that when vibrating string instruments reach a significant popularity, they are acclaimed in Europe during the Renaissance, bringing a great number of compositions for duet, for instance, and a smaller number for lute trio. When the guitar is preferred to the lute in the 19th. century, there were again a lot of pieces performed by duets and trios.

Nevertheless, the possibilities of putting together in a quartet not only lutes but also guitars have been completely avoided. It’s not difficult to understand what were the reasons why when we examine – even if we do it superficially – the existing chamber music literature. Above all, we can see there was almost always a concern with the idea that all different parts of each instrumentalist were equally valued so that none of the musicians felt inferior. What occurred more often was simply inverting voices whenever a part was repeated or changed and this worked out perfectly as far as duets are concerned. When it came to trios other expedients were necessary sometimes to the detriment of the group’s clarity: three instrumental voices had to act within the same tessitura, sounding almost as a competition among them. Having this idea in mind, we can see that the fourth additional guitar would easily cause a sound jam of an indigestable “guitar performance”.

It is interesting to see that there was no attempt to adapt some of the techniques used in compositions for groups of arch instruments where such concern was not that important. And this could not be so, especially because of differences of tessitura (which mostly determines the performance of each instrument), consequently, the global result is more important than the individual splendour. If the last century’s guitarists had been more familiar with the compositions for other instrumental groups, maybe this attitude would have created well structured works for guitar quartets which I believe would have been very popular both in concert rooms and in soirées where musicians and music enthusiasts often met.

Going from conjectures on the past to today’s reality, it is a fact that the extraordinary popularity of the guitar during the second half of the 20th century led to the emergence of a growing variety of guitar ensembles, ranging from acclaimed duets to huge Japanese orchestras with dozens (sometimes hundreds) of guitarists. Obviously, since most of these groups had been recently created, many of them were in an experimental period and it was too early to have a prognosis on their possible evolution. However, it is easily predictable that the guitar orchestras with symphonic dimensions were merely exotic curiosities having more of a visual than an auditive impact. We can also see a guitar duet as a definite formation which adds to the existing vast repertoire from the 16th to the 19th centuries a much greater number of high quality contemporary compositions.

And among the most interesting and promising news of recent times we can undoubtly include experiences that have been conducted by different groups in several countries where a concept of instrumentation adequate for guitar quartet and an appropriate repertoire for this musical background have been developed. Besides having inspired a great number of original compositions they have also given birth to many arrangements from works that had been originally written for other musical groups some of them with surprising results. Contrary to last century’s prevailing instrumentation style, today guitar groups are preferably seen as an organic whole, using a great deal of timbre combinations.

It was with this idea in mind that one adaptation of Villa Lobos’ Bachianas Brasileiras nº1 occurred to me. In such procedures we must think not only in terms of simply making the repertoire bigger by means of an additional arrangement, but there must be above all a good reason for doing so. In this case I wouldn’t say that this piece is better than its original version, that for a cello orchestra, when performed by a guitar quartet, except in parts of the first movement (especially the beginning), which is a clear imitation of “cavaquinho” (a small guitar – a typical Brazilian instrument). This version sounds more natural because of the guitar sonority. Obviously, this is not the case during the biggest part of the second movement where the cello reigns as a sovereign and this is the reason why I first thought this Prelude/Modinha should be eliminated of this guitar version. However, the main reason for this arrangement seems that even though it is one of the most beautiful and original Villa-Lobos’ compositions it has rarely been performed or recorded (I don’t know of any public performance during the last twenty or thirty years) for the simple reason that there haven’t been (maybe not any longer) any cello orchestras. In the early seventies, I remember I was in New York on the day a concert was held at Carnegie Hall in Pablo Casals’ honour where one hundred cellists participated. If I’m right they played only these Bachianas’ second movement. Therefore, without having the intention of making it better but rather thinking it is an opportunity to make it known, a piece which is both rare and beautiful, it is a great pleasure to see it included on this Quaternaglia’s CD.

Sérgio Abreu